DAVID HAYNES

Editor/Founder at Sixteen:Nine

Dave Haynes is the founder and editor of the Sixteen:Nine blog. He is a well-known figure in the digital signage and Digital Out Of Home sectors and runs a pair of companies, The Preset Group and pressDOOH.

“Before we fabricate anything,” says Bill Dunn, as we’re walking into LG MRI’s 120,000 manufacturing plant, “we know that display is going to thrive, not just survive.”

His company, based in the sprawling, heavily-wooded suburbs north of Atlanta, makes large-format outdoor displays for the out of home advertising business and, more recently, emerging markets like fast food drive-thru lanes. LG MRI has about 30,000 units in the field, and based on a plant tour I did last week, there are a lot of new orders getting filled.

The company has about 200 employees, and another 100 at a nearby facility that’s focused on military and commercial aircraft displays. It’s that work, putting screens in the cockpits of everything from big passenger jets to fighter aircraft, that pretty much defines what LG MRI now does. With 100% market share in the North American market, CEO, founder and sole owner Dunn was looking for new markets for specialty displays, and found digital signage.

It’s a very different business.

While the aerospace industry is driven by engineers who, by necessity and DNA, are focused on precision and uptime (screens just can’t dim or die), the out of home industry is run by media people who tend to be focused more on the unit price of displays, and their base look and feel – not their underlying specs.

It makes Dunn crazy. An engineer to the core, he sees complicated, mission-critical jobs being judged and decided on the wrong factors.

LG MRI’s unit prices tend to be significantly higher than the offshore and North American companies it competes against, but Dunn argues the total cost of ownership on outdoor display jobs is almost always wildly higher in going with less engineered product. Where competing displays aren’t meeting advertised specs the moment they’re turned on outside, and will fall below acceptable viewing standards in about three years, Dunn says his company’s displays will last at least 10 years and look as bright and crisp as the day they got powered up.

That lifespan happens, he says, because almost half of the people on staff at LG MRI are engineers. Dunn has 90 kindred spirits who are just as fixated as him on uptime, viewing quality, and process.

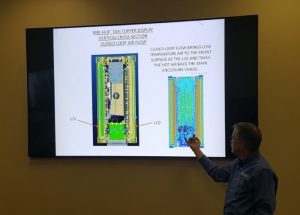

Among the many things Dunn showed me through the better part of a full day at the facility was a demo – dumbed-down for dumb me – on something called computational fluid dynamics. It’s a modeling process, involving very complex, pricey software, that uses data analysis and algorithms to model and resolve designs that, in the case of outdoor displays, examines the generation and movement of heat.

By using what’s abbreviated as CFD, Dunn’s engineers can model and figure out how displays designs will handle and exhaust all the heat that gets generated by the LED lights that drive super-bright outdoor displays, but also the additional, at times crushing heat load of the sun.

“Heat is the enemy,” he says, ” and our job is to figure out how to get rid of all that heat.”

The conventional way to get a screen bright enough to cut through mid-afternoon sun, on a Phoenix sidewalk, in July, is to crank up the backlighting and overpower the sun’s rays, and then power a bank of fans and filters in the enclosure to keep the display within acceptable operating temperature ranges.

Dunn says that design leads to heat building up and staying trapped inside the core enclosure that houses the critical electronic components, like the display controllers and media players. His team has learned through experience, and validated through computer modeling, progressive generations of designs that move heat through the enclosure and exhaust it, while keeping the electronics isolated and relatively cool in their own sealed air pockets. Between LG MRI and the sister company, American Panel Corporation, there are some 300 patents.

Part of the work and knowledge is based on having sorted out ways to optimize display performance.

Dunn and his guys set up a demo out back of the Alpharetta plant, in the direct morning sun, to show how an LG MRI display performed against a competing product. Both, Dunn says, look great in a showroom or on a trade show floor. But real world conditions are a different matter.

LG MRI’s display is rated at 3,500 lumens, and at 10 am on a bright, warm morning, the external measuring tool read 3,490 nits. The screen beside it, from a major manufacturer, is rated at 2,500, but was actually pushing out 1,540 nits – because of a filter that’s part of the screen design to fight reflection, and because the display was already fighting the sun, heating up and taxing the fans and available power.

What was kind of amazing was measuring the brightness from a 45 degree angle, which is how a lot of people are going to see screens when they are walking past an ad display built into a bus shelter or sitting ahead of them in a drive-thru lane.

Brightness on the LG MRI screen went down to 2,320 nits. It went down to 381 nits on the brand X display, and the display’s visuals were barely visible.

Dunn says that brightness difference, as compelling as it may be, isn’t even the real issue. While the display industry sells on brightness levels, the real measure to care about is contrast. Contrast readings have to clear a certain bar, or viewers aren’t going to be able to distinguish much of what they see on a sunlight-bathed screen.

The pix I took didn’t do a great job of showing differences. But my own take was the LG MRI screens were definitely brighter, had a much wider viewing cone and the one in the middle from the pic above, from another manufacturer, had a purple haze to it, brought on by the filter in the glass.

I’ve been at other facilities where specialty displays are put together, but can’t fairly comment on whether what LG MRI has and does is wildly different. I can say it was impressive. My unschooled idea of the outdoor specialty display business is buying open-frame high bright displays and building them out back of the offices into environmentally protected, mechanically cooled enclosures.

I’ve been at other facilities where specialty displays are put together, but can’t fairly comment on whether what LG MRI has and does is wildly different. I can say it was impressive. My unschooled idea of the outdoor specialty display business is buying open-frame high bright displays and building them out back of the offices into environmentally protected, mechanically cooled enclosures.

The LG MRI guys, however, pretty much start from scratch.

The first thing I saw was a robotics line that builds the integrated circuit boards from the raw, green wafers, and then seals and bakes them. The same line produces the boards for, among many things, F-35 fighters and M1 Abrams tanks.

In the main plant, which is about the size of a Costco, LG MRI builds displays up from the raw LCD cell (think a sheet of film) through the LED backlighting layer, circuitry, custom wiring harnesses, metalwork and glass. The facility has giant laser and water jet cutting machines, a series of Italian machines that do semi-automated precision metal bending, and a crazy vacuum sealer bag thingie that pulls sealed layers together without putting weight on them.

The optical glass that is used to front displays was previously outsourced, but a whole assembly line is now being built that will bring all that in-house within a month – going from raw mother glass sheets through cutting, polishing, painting and curing.

The company even has a wood shop making its own custom shipping crates for the giant displays. But before they get packed, every unit goes through a quality control process that includes time in a shower to verify its water tightness. Funnily, on a floor packed with robotics and precision tools, the best way to dry off a wet display was a guy, a ladder and a leaf blower.

In the digital signage business, sticker price is the irrational driver behind everything from hardware and software to installation deals. There’s always a healthy chunk of end-user/buyers who don’t really know what they’re looking at and buying. So they revert to comparing base specs or appealing visuals in making decisions.

Sales guys with “premium” products make the Total Cost of Ownership argument, but a percentage of the buying market thinks they can get what looks to be pretty much the same thing – whatever that thing is – for less.

I’ve had may conversations with the heads of software companies who say a big part of trade for them is replacing the first system that went in, and went badly. Dunn says the same thing happens, as they get calls from media companies that opted for lower initial costs and learned the hard way that the cost ended being far higher – between installation complications, rolling trucks and techs for servicing and repairs, and the screens dimming out by the third year.

Smart and/or seasoned buyers do things like shootouts. Dunn was up in the Toronto area last week watching a drive-thru install at an outlet of a major QSR chain – pitting his pre-sell and menu displays against three other vendors. I was able to get down to Atlanta because I hitchhiked back with him on his company’s six-seater plane, which Dunn personally flies.

I’ve also had conversations with digital hardware companies who say their best sales tool is a site visit. I visited a custom PC maker last fall, and their folks said if they got prospects to come out for a tour, the close rate on deals was just about 100%.

Dunn confirmed that the same thing happens when his sales team get prospects to brave Atlanta traffic and make their way up to the plant.

I can see that. What you have is a military-grade supplier applying that military spec and mindset. It’s the difference between “it should work” and “it has to work.”

I can remember, years ago in my dark and mercifully brief sales past, staring dumbstruck at a software developer who told me a critical feature was ready, faster than expected, for a monster client that I was trying to close.

“You’ve tested it?” I asked.

“It should work,” he replied.

He didn’t even know he was having a near-death experience.

In this case, if you are a media company putting a 75-inch display on the end of a sidewalk transit shelter, that cost $20K-plus, it’s just got to work. And work well, And look great. For years.

And with 70% of sales at many QSRs being based on drive-thru lanes, a screen that gets dim or dark is a screen that’s losing sales.

The thrive and not just survive thing Dunn mentioned as we walked into his plant definitely makes sense.

The LG in LG MRI, by the way, is THAT LG. The two companies have a joint venture, and LG’s display technology is central to the product line. The electronics giant has some staff on site in Georgia, but the company is owned and run by Dunn. There are also some products that are marketed as MRI, that are not part of the LG partnership.

This article has been reposted with permission from the Sixteen:Nine blog.